The Curious Case of Ebola's Phylogenetics, Part III

“Mankind has only one science…it's the science of discontent.”

Please consider reading Part I and Part II so you don’t get lost.

The past few years have been rough for my view of science. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, I really did believe trained investigators using good methods were quite likely to get right answers even if they had professional incentives perhaps to not do so. I do inference from data for a living and have worked in a variety of different industries. I’ve felt pressure to make results go a certain way, or to overstate claims. I assumed this was a product of the profit motive of business and academic scientists would be less vulnerable to these failures modes.

Obviously, it’s apparent this was the opposite of the truth. In business, if you defraud people you can go to jail, especially if those people are wealthy, connected, political dupes. In science, if you defraud people, you can sue your critics and instigate a protracted legal battle for eight-figure stakes.

The first and second part of this series demonstrated what seems to be unusual publication behavior among scientists in the early months of the 2014 West Africa Ebola epidemic. There was a rapid uniformity among opinion and methods used in scientific papers studying these events. The authors who did any phylogenetic analysis used an unwarranted technical appeal to a statistical phenomenon called “long branch attraction” to levy a narrative that this novel Ebola strain actually looked like past strains. They may even have been correct that it did, but they didn’t know that at the time.

I finished Part II with a reference to Gire et al., 2014, the second most-cited paper in the literature after Baize et al., 2014. This poast will not be a long dissection of scientific papers like Part II, but we’re going to start there.

Gire et al.

This paper is an event. In Science, with almost sixty different authors, it’s the capstone project of the Ebola outbreak. Moreover, it was clearly intended to be such a capstone project.

In Figure 2, I estimated the H-indices of the authors in 2014 and 2024 by way of google scholar.

In 2014, the average author on Gire et al. had an H-index of 27. At that time Eric Lander only had an H-index of 251. To account for the Lander effect, consider the median H-index, which was 10.

This was a high profile group of authors. It’s a Medley of well-heeled Bostonians from Harvard, MIT, and the Broad Institute. Many are affiliated with the Kenema Government hospital, which we’ll examine later. After Lander, Andrew Rambaut was the highest ranking scholar at 100, followed by, of course, Bob Garry at 50. The paper summarizes the entire work of Dudas and Rambaut and Calvignac-Spencer et al. in the following terse snippet.

Rooting the phylogeny using divergence from other ebolavirus genomes is problematic.

Given the score of hours I put into the analysis in Part II, reading this lone sentence in Science does chafe a bit.

This isn’t even a research paper—Science classifies it as a “report”, and it should, given its puny technical girth. It’s a signatory letter. These guys aren’t bouncing the rubble of the Ebola virus outbreak with the authors’ prestige; they're nuking the rubble. A co-author and head of the Ebola effort in Sierra Leone was a clinician named Sheikh Umar Khan who died of Ebola on July 29th, 2014, less than a month before the paper was published. Stunningly, the manuscript references the fact that four other listed co-authors died of Ebola. Obviously, this is not normal scientific communications.

As far as I’m aware, there’s no major issue concerning the events of the West Africa Ebola outbreak covered in Gire et al. that meaningfully gets challenged by subsequent scientific literature. This report is treated by history as Gospel.

The Lander Issue

For those of you with no reason to know, Eric Lander is biology’s biggest swinging dick. As of writing this poast, and it might change tomorrow, his H-index is 318. For a frame of reference, 60 is considered pretty high-rolling in biology. He has over a thousand publications, he’s led the Broad Institute, the Whitehead institute, and collected a MacArthur genius grant on the weekend. He’s written about everything from projective modules (cursed be short exact sequences) to proteomics. Forget Brady or Big Papi, this guy owns Boston.

The question that will serve as an outline to the rest of this poast is “Why is Eric Lander a co-author on this paper?”. Unfortunately, Lander’s biography, while potentially being the key clue to this puzzle, simultaneously complicates answering this question given how expansive it is. We’ll examine four possible answers for this, the evidence supporting those answers, and the interpretations of those answers for what happened in West Africa in 2014.

1. Lander as a technical expert

I checked both manually and programmatically: even given Lander’s dizzyingly wide-ranging career by 2014, he had never co-authored a paper concerning viruses or even infectious diseases before Gire et al. He’s since had a few publications about SARS2 spike protein interactions, but that’s basically it. When I brought this issue up to an principal investigator I know, they pointed out that often these large multidisciplinary teams will bring in a very specialized subject matter expert to sign off on one particular section of the manuscript.

The problem with this idea is that Gire et al. doesn’t have much in the way of novel technical analysis over the previous publications. It’s a highly manicured and stream lined summary of the previous publications, categorized by Science as a “report”. Many of its senior authors are authors on previous Ebola publications, like Andrew Rambaut. Eric Lander may be smart, but he’s not needed on this paper.

This model of events is unlikely, but if true, makes Lander’s co-authorship look innocuous and divorced from any sort of irregular publication.

2. Lander as a political closer

Suppose Gire et al. faced a publication hurdle. Publication in Science is a big deal and even elite authors with good manuscripts can face grinding uphill publication circumstances. Pardis Sabeti was a co-author and investigator at the Broad Institute which did the then pioneering work of rapid sequencing at scale to track the origin and progress of viral outbreaks. Remember, the title of the manuscript is “Genomic surveillance elucidates Ebola virus origin and transmission during the 2014 outbreak”. The sequencing technology brought to bear on the SARS-COV-2 pandemic has made us take all of this work completely for granted, but this was a huge deal eleven years ago, especially in a country with uneven healthcare infrastructure like the United States Sierra Leone.

There were several other co-authors on this report at the Broad including lead author Stephen Gire. It stands to reason any one of them could have asked Lander, their boss, to lend his imprimatur to the paper to get it over the finish line, and he did just that.

This seems much more likely than the first option, but neither explain what was covered in Parts I and II: the curious methodological choices leading up to Gire et al., the stringent exclusion of standard phylogenetic methods, and the seeming bias to make the Makona strain look more like historical strains of ebola.

3. Lander as a culpable bureaucrat

The primary western scientific outpost during the 2014 West African Ebola outbreak was the Kenema Government Hospital. In his politically blustery but factually on point book The Ebola Outbreak in West Africa, Chernoh Bah recounts the series of events leading up to the epidemic after the CDC recategorized Lassa fever as a “Category A” pathogen.

This CDC classification turned Lassa fever into a threat against United States national security interests. This eventually resulted in serious international actions: a significant amount of the billions of dollars that were raised and set aside by the United State government for biodefense efforts were the anthrax incident in 2001 was now channeled towards laboratory research effort in West Africa located at the Kenema Government Hospital in eastern Sierra Leone.

…

The amount of biodefense dollars that flowed into Sierra Leone from 2009-2012 instantly transformed the once dilapidated and abandoned Lassa Ward of the Kenema Government Hospital, located on its small site in eastern Sierra Leone, into a considerable recipient of a well-funded international research program.

In other words, a US defense initiative turned a run-down, poorly-funded foreign laboratory with appalling biocontainment protocols into a up-kept, well-funded foreign laboratory with appalling biocontainment protocols.

Long story short, the Kenema Government Hospital partnered with an international cutout called the Viral Hemorrhagic Fever Consortium which partnered with Lander’s Broad Institute in Cambridge, MA. The KGH also partnered with the biotechnology company Metabiota, which was excoriated in an MSF report for shutting its books and not cooperating with foreign medical authorities when the disease appeared in Sierra Leone.

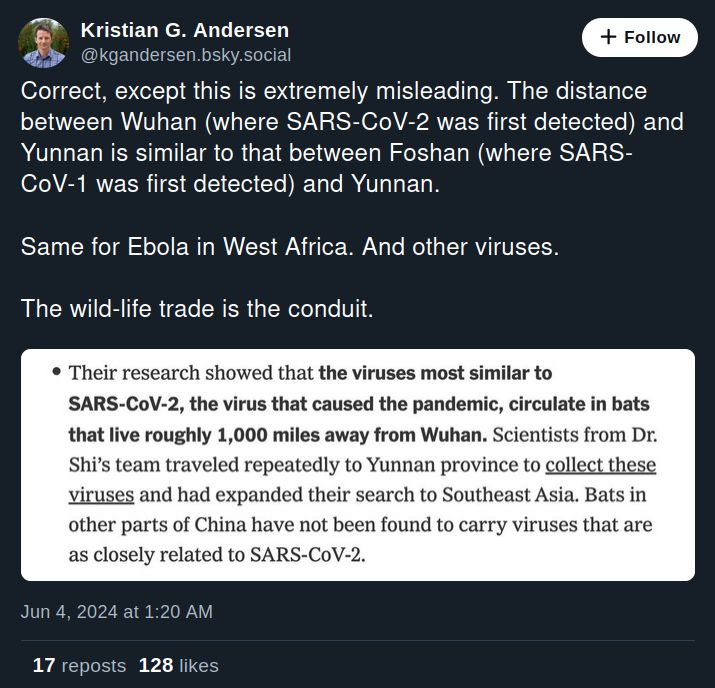

Astonishingly, the VHFC, to this day, is headed by Gire et al. co-authors Bob Garry and Kristen Andersen, and of “Proximal Origins” fame.

In this Eric Lander model, Latham and Husseini are correct: the West Africa Ebola outbreak began in Sierra Leone, not in Guinea, as a lab escape from research at the KGH lab. The subsequent literature overviewed in Part II developed to obscure this fact by hastily insisting the novel Makona strain belonged in the known ZEBOV clade. If scientific papers had determined, alternatively, that Makona formed a separate clade or potentially formed a separate clade, more scrutiny would have had to be applied to the issue of Makona’s provenance. These papers culminated in Gire et al. which Lander co-authored bringing all his scientific authority to bear on the issue. He thereby contributed to a scientific exculpation of his partner organization and his own organization in events leading up an outbreak that killed thousands of people.

To be clear, he didn’t even need to be sure such an escape occurred at the KGH, but under this hypothetical, he could still have steered scrutiny away from this possibility in deciding to co-author Gire et al.

Obviously, this is a very disturbing possibility. Under this scenario western scientists happily did dangerous research under third world lab containment procedures surrounded by third world healthcare infrastructure, and colleagues of those scientists were complicit in concealing these facts in the form of published scientific papers.

I actually don’t completely endorse this view. One reason Makona leads to a confused phylogenetic analysis is that it is very different from published ZEBOV strains. If this was the result of a research related incident at KGH, this divergent strain would have to be there. Where did this divergent strain come from? If it was discovered in the bush and brought into a research setting, why wasn’t it published? I’m not aware of any published result confirming ebolavirus at KGH, but last year Kristian Andersen did somewhat obliquely refer to work on Ebola there.

Maybe Makona was the result of passaging experiments on a more inlying ZEBOV strain. I have no idea why anyone would do this. Culturing ebolavirus under inadequate biocontainment is dangerous; culturing a passaged strain under those conditions seems suicidal. More unanswered questions.

4. Lander as a government apparatchik

Yet another wing of Eric Lander’s CV houses an eight year stint as the chair of Obama’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology, a period covering the 2014 outbreak. He’s co-signed reports in this capacity on biosecurity issues. In 2022, Lander had to resign from government, apparently for being an asshole, which speaks volumes about how important people treat and are treated when they only exist within academic walls.

In his book, Bah describes in detail how the authorities in West Africa mishandled the management of the outbreak and oversaw destabilizing unrest.

National diseases controls laws passed by local authorities in a belated response to contain the outbreak affected individual freedoms and worsened people’s daily lives. In Monrovia’s West Point community angry crowds broke the governments’s quarantine and stormed a nearby treatment center, looting beds and mattresses and releasing the patients housed within its walls. In the Kono and Kenema districts of Sierra Leone, angry youths equally revolted against health care workers and attempted to burn down treatment centers alleging that Ebola was being spread deliberately.

…

Leaders of the affected countries immediately convened an extraordinary summit of the Mano River Union presidents on Conakry on August 1, 2014 to discuss the unfolding protests and the epidemic.

…

In Washington, Obama announced the deployment of a United States military force of 3,000 troops in Monrovia to be commanded by Major General Darryl A. Williams, Commander of the United States Army’s Africa Command (AFRICOM).

Nearly a month before Gire et al. was published in Science, the outbreak had reached geopolitical proportions, encompassing the US military.

Given the background of these circumstances, Lander may have been pressed upon by two possible sources:

In July, 2014, Tulane University was instructed by the medical authorities in Sierra Leone to stop all ebolavirus testing. Tulane was partnered with VHFC and the Broad. Given this precedent of obstruction from the government in Sierra Leone, Lander felt pressure to rubberstamp the learned findings in Gire et al. to smooth relations between KGA and western partners. It would have been calamitous for the Broad to be publicly kicked out of Kenema if Lander did not endorse the politically convenient theory of his governmental hosts, including that the disease started in Guinea, not Sierra Leone.

Obama was Lander’s boss, and the administration could have pressed him to co-author Gire et al., The Official Paper, to narratively manage the crisis in Sierra Leone.

What’s interesting is that either of these, with Lander acting in government interest, is plausible regardless of how ebola came to West Africa.

Going Forward

Obviously, unlike Parts I and II, a lot of this is speculative. The only firm conclusion I can confidently posit in this series is there was an unwarranted certainty and consensus in the early scientific regarding the ebolavirus epidemic and this certainty was fostered to make the outbreak look more like previous ebolavirus outbreaks. I don’t think we have a good idea of what happened early on, and under innocent assumptions, involved scientists definitely don’t.

In the year of our Lord 2024, ten years after the ebolavirus outbreak, Andersen, a co-author on Gire et al, sponsor of the learned theory, apparently thinks that wildlife traders brought bats or some other host animal from the Congo Valley to West Africa in the early 2000s. Did those infected animals they brought infect people? Of course not! They must have escaped or something and infected indigenous bats and after a dozen or so years, an infant boy in Guinea was playing in a tree with the infected bats and that caused an outbreak that killed thousands of people across four or five different countries.

I don’t know what to tell you. This entire story is made up. This motivated and retrofitted reasoning of course came to govern the early SARS-COV-2 literature by the pens of the same authors. The wheel turns and nothing is ever new.

The motives of the lead scientists involved are opaque and could have involved any of the four scenarios I outlined or even hybrid scenarios of those four. An investigator bolder and more capable than I am should try the following avenues.

Eric Lander needs to be asked what his contribution to Gire et al. actually was.

Eric Lander needs to be asked if he has or has ever had a security clearance.

Eric Lander needs to be asked if he was ever given information about the ebola outbreak in West Africa from the intelligence community.

Eric Lander needs to be asked if he had contact with non-health affiliated authorities in Sierra Leone, and what the nature of that contact was.

Eric Lander’s government communications from this period need to be FOIA’ed and scrutinized. Given the web of research incest this guy oversaw, and his probably ten or so email addresses, probably nothing would be found, but it’s worth doing.

Executive branch records related to Metabiota need to be FOIA’ed and scrutinized.

Andersen and Garry (in the news again today!) need to be asked whether ebola was being studied at the Kenema lab, and if so, where did the strain they were using originate. If so, what grant was this work done under?

Andersen and Garry need to be asked about their view on the ethics of conducting dangerous research inside vulnerable communities in clear, admitted efforts to thwart US biosafety regulations.

I hope you enjoyed this series! If you have questions about the technical work in any of these poasts, please message me and I can point you to code and data that went into the series.

A very interesting series, hope to see a Part IV.

"Maybe Makona was the result of passaging experiments on a more inlying ZEBOV strain."

Some time ago I had a look at the origin of Makona. I'm very open-minded to such a possibility, but had to conclude there was no way it could have been derived from any known (*published) strain - no matter how many passages. I lean towards a scenario in which the pathogen discovery side of the Kenema lab (Metabiota) perhaps brought something novel back from a Congo expedition.

Maybe there is something to garnered through FOIA?

very interesting, you know too much, and you write well.