What’s happening with the cuts to the NIH, CDC, and public health writ large in Washington is, I think, not mysterious. The new administration is determined to purge ideological enemies, and those enemies exist in agencies allied with the opposition party. To the extent DOGE and the broader administration don’t part ways, in their eyes, USAID was emblematic of unaccountable elements in the executive branch, and the public health infrastructure is not much different.

So if the administration is making these cuts for self-interested reasons rather than reformist ones, apart from plummeting real estate prices in Bethesda, what are the effects going to be? For its part, last night 60 Minutes decided to feature Francis Collins outlining the dire public health outcomes should the diet HHS is on continue, and last week they brought on the irrepressible Angela Rasmussen to warn about poor preparation should a bird flu pandemic develop.

DOGE’s approach is right for the wrong reasons. Their reasons are straightforwardly vindictive, but this essay will argue that after this past pandemic, public health’s relationship to combatting infectious diseases as currently conceived by the US government should simply be retired. This is a radical position, but I never want to hear from Francis Collins or his ilk again. I’m going to explain why.

What is public health?

The practice of public health aims to improve outcomes to societal health through centralization. When you go to the doctor for advice because you’re sick, that’s obviously decentralized, because the doctor’s advice is for you alone. In fact, in many ways we’ve structured doctor-patient relations to be isolated from the rest of the health care system through HIPPA, confidentiality, and other methods. The practice of modern medicine itself is almost by definition private health, not pubic health.

The centralization tendency runs in many separate channels, but it’s always the main aim of the public health authorities. Institutions gather extensive data on health practices and outcomes, and gathering data is centralizing by its nature. Standardized recommendations are deployed. We all remember the food pyramid. The public facing recommendations a health agency makes are centralized through some sort of credentialed and bureaucratic prestige process to ensure the agency speaks with a single voice. The CDC has a long page of advice about how to do this and how it works written for people working in health comms during a crisis. It states explicitly

You will need permission from the health authorities in the jurisdiction where the outbreak is occurring before you speak directly with any media. Unless you have that permission, you should direct anyone requesting an interview to the health authority in charge. Also, ensure you know your organization’s policies regarding communications with the media … Consult a communications expert assigned to the outbreak investigation about policies and prior clearances needed. Know your boundaries.

So, during a crisis, what is the goal of a public health agency?

Is it to inform the public about what is known about the threat or to mitigate panic?Public health is currently part of the state and all states hate panics because panics topple states. But, if they believed masks and PPE and whatever really worked, why wouldn’t the authorities engineer a run on PPE to make sure everyone masked up? They’d be telling the truth about what’s known and creating panic at the same time. This is a conflict of interest, a contradiction in goals.

I actually don’t know what the goals are. Early during COVID, it wasn’t clear what these people were doing, but the centralizing tendency of the US public health response ensured that at any given time, there was an attempted uniformity of messaging. Lack of centralization means lack of uniformity which means discord. Whatever the goals were, they were pursued through centralized means.

You might object that we have federalism in this country and there’s not a fixed set of centralized national standards in public health. There are many other developed countries that don’t really have federalism, but fair enough. Imagine a world where there was no organized common response at all. If people got sick with COVID, they went to their doctor. If they got really sick they went to the ER, and which did the best job it could to save them. Maybe hospitals noticed there were a lot of people sick with atypical pneumonia and tried to ramp up bed space or PPE or ventilators, but that was it. We never saw Anthony Fauci behind a podium and Donald Trump didn’t tout bleach.

This would be insane. State governments needed to stockpile PPE, make sure there were enough hospital beds, and decide whether to shut businesses and close schools. So even with a distributed federalism, there was centralization in governments’ responses.

So the data collection is centralizing, the communications are centralized. What about the decisions themselves? Later into 2020, people who dissented were subject to secretive censure that was mounted by the most central US public health cabal.

In the case of COVID, the goal was social influence; less euphemistically, it was manipulation. This isn’t the CCP (more on that later); Fauci and Collins couldn’t just roll the tanks in to deal with the problem. For example, people needed to sort of agree to abide by stay at home orders. To do pull that off, you can’t have pesky fringe thinkers on CNN poisoning peoples thoughts about why their business was closed or why their kindergartners are taking Zoom calls. You need consensus, harmonization, centralization. I think that’s what public health is basically about.

Specific COVID takeaways

There have been many, many, many, many, many, many public health fumbles, fuckups, and floundering over the past five years. Excuses were made for all of them.

Some of these deserve their own commission, and certainly at least a book, but we’re going to do the lived experience thing here right now. The school closures and lockdowns were the single most disruptive event in my entire life, and the most catastrophic folly of the public health authorities we witnessed. My career was set back. I lost a job I loved in March of 2020, which was two months before my wife gave birth to our second son. Our first son was 2 years old when that happened. The daycares closed. Fortunately, he didn’t really have any idea what was going on. The people who really had it hard were those who had school-aged children WHO WERE FORCED TO SUPERVISE GRADE SCHOOLERS ON ZOOM CALLS WHILE THEY TRIED TO WORK. Oh, and I forgot the kids who never saw their friends and the people who had loved ones die alone.

Most mornings in March and April, I would leave my super pregnant wife working at her desk and take my 2 year old son in a stroller to the park, hoping the weather would get warmer faster than it was. One time a guy honked and yelled at me out his window because I wasn’t wearing a mask outside. My son got confused and upset.

I’m an equanimous person, and I’m going to be on my best behavior for the rest of this poast, but this set of public health decisions still infuriates me to this day. I will not countenance Timothy Lee’s nakedly partisan assertions that these policies were Trump’s fault.

To my eye, the US public health decision-makers mostly imported these policies from China, which implemented lockdowns in on January 23rd. We forget now that Trump started a trade war with China his first term, but he apparently exempted the import of asinine communist ideas from tariffs. There had been a great deal of skepticism in public health circles that invasive measures like quarantines or aggressive social distancing “worked” broadly speaking, but in a crisis and with an example set by the CCP, cheerled by the WHO, these views did not win the day in the West.

Regarding these decisions, most people will remember Francis Collins had to make just about the most embarrassing, cringiest mea culpa ever at the end of 2023. If you forgot, let’s refresh your memory.

The public health people — we talked about this earlier and this really important point — if you’re a public health person and you’re trying to make a decision, you have this very narrow view of what the right decision is. And that is something that will save a life; it doesn’t matter what else happens. So you attach infinite value to stopping the disease and saving a life. You attach zero value to whether this actually totally disrupts people’s lives, ruins the economy, and has many kids kept out of school in a way that they never quite recover from. So, yeah, collateral damage. This is a public health mindset.

So, yeah, collateral damage.

Much of the study of public policy involves costs and benefits. That’s also true of life more broadly. There just aren’t very many Pareto improvements to be made. In a world more perfect than our own, policymakers try to weigh those costs and benefits. Often they don’t. Sometimes they’re captured, or bought off, or ideologically blinkered. To hear Collins state that that his entire field didn’t even consider the 13-figure costs of their policy recommendations betrays an unalloyed species of systemic stupidity. This was “a public health mindset”. To only consider the benefits and not the costs of decisions is the mindset of a meth head and meth heads ought not make trillion dollar decisions. To hear him panhandling for US public heath schmoozing with a vacuous reporter after this performance on 60 Minutes is galling.

Look. Sheilagh Ogilvie’s recently wrote a great book called Controlling Contagion that documents the historical withdrawal of people from markets and social interactions in the times of plagues. Not surprisingly, plagues are hard on economies whether they’re developed economies or not; regardless of public health proscriptions, people withdraw. Maybe I’m wrong and this withdrawal would have happened to the same extent without the lockdowns, but I doubt it given what we know about Sweden’s approach. In their book In Covid’s Wake, Macedo and Lee look at statewide evidence and demonstrate that US states’ policies were determined by partisan valence, not by epidemiological circumstances. They also note that all US states’ had roughly similar COVID performance from a mortality and morbidity perspective regardless of their policy choices.

So the decisions were political and had no discernible impact on the variables they cared about.

Public health officials didn’t just not weigh uncertain benefits of non-pharmaceutical interventions against quite certain costs of crashing the economy: they ignored the quite certain costs completely.

America is not the world. The lockdowns and closures weren’t just a disaster for the United States. In a return to form of the late 1950s, communist innovators who designed these mitigation strategies eventually oversaw the deaths of several million people when protests forced them to swiftly reopen the Chinese economy. Even with the dystopian state capacity the CCP boasts, there was no successful implementation of these sorts of NPIs anywhere on earth.

They’re not sending their best

So what happened to public health? A major issue here is perhaps the people who have gone into the field have gotten dumber. One doctor I spoke with about this unabashedly claimed public health is now filled with people who could not get into medical school.

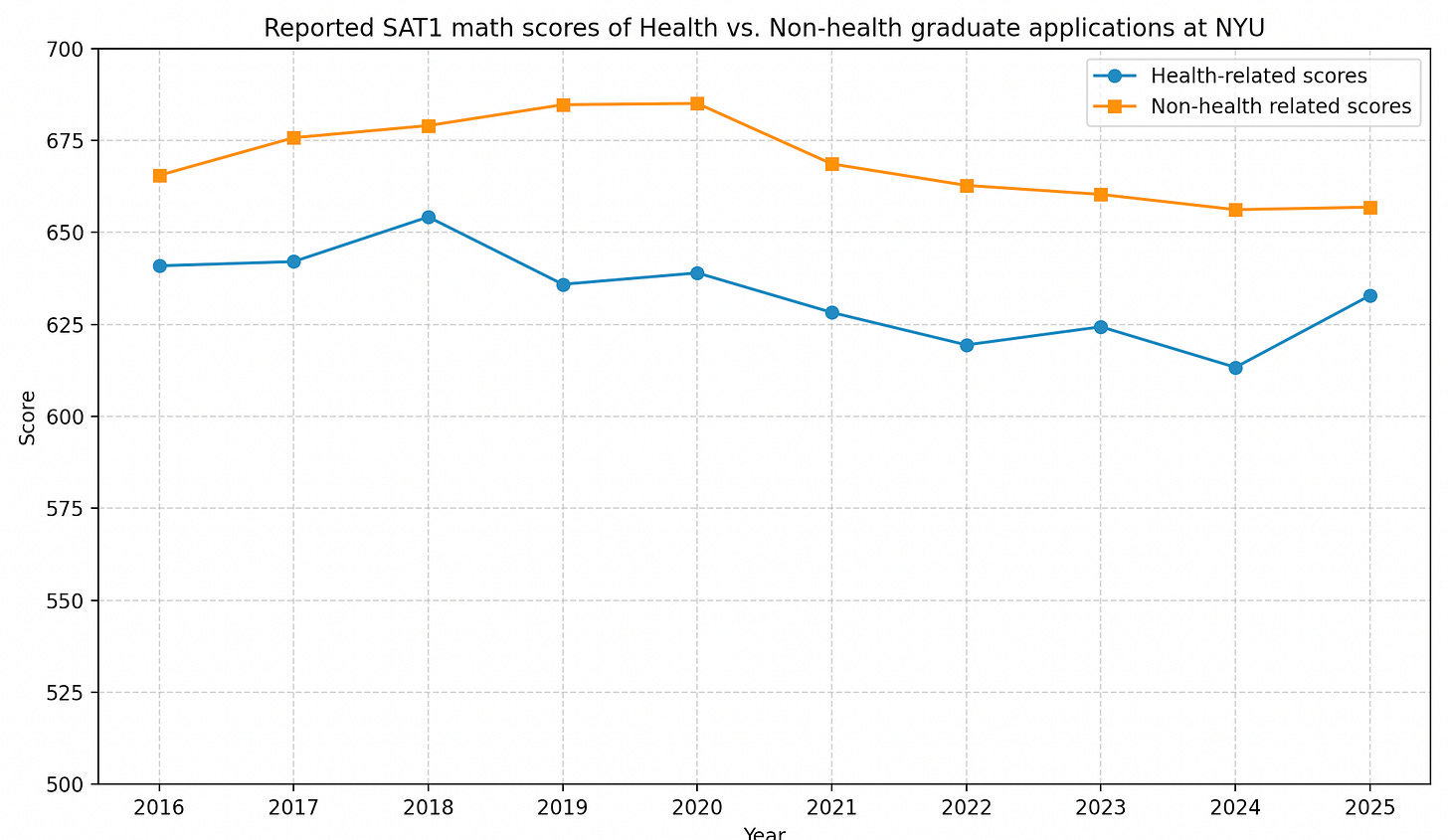

I wrote about the NYU data breach in March. Unbelievably, the breach was practically ignored by everyone except as tool to dunk on questionable admissions practices. The data is useful for other things! I looked at NYU’s reported standardized test scores for graduate applications in health related programs versus all other graduate programs. These are programs described in the data as “Community Health”, “Health Policy & Management”, “Health Policy Analysis”, “MSW/MPH Public Health” etc.

So I’m not sure I buy the narrative that they’re getting dumber faster than other graduate students, but they’re certainly starting out at a lower level than your typical NYU graduate student, and it’s been that way for a decade. The reading scores tell a slightly different story.

The other aspect of this worth noting is the extraordinary sex ratios in the applications to these public health programs.

A lot of academia has become increasingly feminized. I don’t really view this as a bad thing. However, if you don’t believe this gender composition affects aggregate attitudes toward public health risk and tradeoffs that eventually moves downstream into government policy, I have a bridge to sell you.

This is probably related to a change in focus in public health syllabi as well. Academia writ large has an interest in equity now, and public health is no different.

Could the system be reformed with just a curriculum change? Possibly. In the spirit of charity, it’s worth considering that people at the CDC just lacked basic training to understand the crisis that engulfed us in 2020. Maybe the DOGE cuts could affect change to this end. I don’t know.

One of the most interesting things about Figure 3 above is how persistent the gap in scores is over time, even when a global public health crisis occurs in the middle of the series. You might imagine that a pandemic might inspire more talented young people to go into public health, or you might alternatively imagine the talented students driven out, dispirited by the field’s checkered relationship to the pandemic response. Nope, static, business as usual, year over year. If a pandemic can’t change the quality of human capital flowing into public health, what reforms could actually work?

What’s next?

I opened by proposing a radical retirement of current government public health infrastructure. We’ve discussed its problems and dunked on Francis Collins a bit, but now I’d like to defend that.

In Andromeda Strain, Crichton imagines a secret military program called “Wildfire” which gets activated in the presence of dire biological threats. A predetermined group of elite scientists who are not bureaucrats is notified and are given unlimited taxpayer-funded resources to deal with the problem.

There’s a lot to like about a model like this in the case that Rasmussen is right and we’re a few chicken nuggets away from a bird flu pandemic. Obviously, making the team and program a military secret would be unacceptable, but the executive publicly predetermining a small group of people who would be in charge and explicitly giving them executive authority to deal with the problem would be a step forward.

An aside on the secrecy point: I know a bit about the history of the early pandemic, but I’m not aware of the exact reason why Anthony Fauci was the one who made it to the White House podium and turned from obscure scientific mandarin to a bobble-head doll. Fauci funded research and managed a bureaucracy. Wasn’t it the CDC’s job to lead the US’s efforts combatting a novel infectious threat? Does anyone know the answer to this question? Was Fauci’s ascension just ad hoc? I don’t know. In my model, this would not be the case, and people in government would know who would be running things at the very beginning.

Who would be on this team? America has tremendous pools of skilled human capital. The problem is that most of these people have better things to do than climbing to the top of a bureaucracy. Many of them are skilled at recruiting talent and building an org to address a specific problem. I remember there was talk of Balaji Srinivasan being asked to run the pandemic response in early 2020. If you absolutely insisted these people be academics and not tech bros, I’ll name names.

Steve Hsu, Michael Mina, Susan Athey, George Church, Ed Boyd, Nick Patterson, Jennifer Doudna, Philipp Tetlock, Jonathan Weissman, Michael Kremer would be candidates. Many are successful outside of academia in their own right. I know a few younger people in biotech personally who I would trust with this job. It’s not that there’s no one who could do it. It’s that they’re currently too busy to make this a full time effort. Hopefully, that would be not be true if there really was a burgeoning bird flu pandemic, and they would commit to dropping whatever they were doing and serve the public. Cincinnatus was drawn from his farm to deal with an existential crisis during the Roman republic. That could be adopted here.

To frame the replacement of current government health infrastructure in a less radical light, I think most people basically understand now that biological or pandemic threats have too many degrees of freedom to be competently dealt with by a lumbering bureaucracy. If a infectious outbreak has an R0 of 4 and not 2, there are different implications for a response. Suppose it’s spread not just through the air but also by water: different implications in how we would respond. When the threat comes, it’s just easier to build the response infrastructure from scratch, tailored to the particulars of the threat. The first part of this essay described public health as essentially centralizing. Maybe there’s no way around that, but whatever the center ends up being, it needs to be as ruthlessly effective at possible.

So yes, most of the functions of the CDC should be wound down. To the extent that the NIH is a stakeholder in public health proscriptions, that should be shuttered. Until the FDA clarifies, modernizes, and improves its stance on human challenge trials, it should not have any authority in that space. The academic labs doing the sort of monitoring and data collection relevant to public health should be funded, and probably better funded than they actually are right now.

Coda

I’m still angry about this subject, but I tried to transmute my feelings into an articulated anger here. If there’s anyone reading this with more influence than me like the mailman or the guy running Panda Express, please contact the people I listed above to see if they would be willing to help. In the current climate, there really are opportunities to improve the quality of our leadership capabilities, and it would be horrific to live through the chaos of the current administration and see those chances squandered.

What happened to all the uber-competent people you read about in books like Preston’s The Hot Zone — the ones at the CDC and USAMRIID in the ’80s and ’90s? Growing up, I dreamed of becoming a virologist working in a Level 4 facility, doing cutting-edge research and tackling high-stakes public health mysteries. I’m pretty heartbroken about where we’ve ended up. I too wonder: how do we get back to that vision of civic-minded, scientific excellence?