Irwin H. Fishbein died this week, aged 93. I knew him well, though I won’t fill you in on the details. Unless you’re of a certain age and run in rabbinic or interfaith circles, you’ve probably never heard of him, but he was the most important rabbi you’ve never heard of, and I loved him. I’ll explain why, and I’ll tell you a little bit of what I know of his life.

When a Mensch loves a Woman

Exogamy, marriage outside of the Jewish faith, has been taboo for millennia and illegal under mainstream interpretations of Jewish law for most of that time. The deep reasons for this attitude are inscrutable; many other cultures have been largely endogamous (think of Parsis or Brahmin castes), but perhaps Jews’ self-image as a legalistically defined nation made endogamy something more than just a custom. Exogamy is still pretty rare in Israel to this day, and the Jewish community’s outsized prominence has made the taboo against it penetrate popular culture thoroughly from Woody Allen to Seinfeld to a narrative arc in Sex and the City.

Most people think the spirit of reform Judaism originated in Europe sometime in the middle of the 19th century. This movement encouraged a measure of individual autonomy applying Jewish law to modern circumstances, but even this relaxation of strictures did not overcome the hard set tradition of Jewish endogamy. Reform Jews, Conservative Jews, and Orthodox Jews alike continued to marry among themselves, those who didn’t faced social ostracism.

That was until Irwin Fishbein arrived on the rabbinic scene nearly a century later.

Young Irwin

Descended from Lithuanian Jews who escaped the pogroms, he grew up in Providence during the depression in an observant household. It was not glamorous. He made it to Brown and then Hebrew Union College for rabbinical school. Though he did hold several congregational positions thereafter, he was also deeply interested in family therapy and how this intersected with his rabbinical duties.

He was committed to civil rights and participated in some of the marches of the 1960’s, including the 1963 March on Washington. It may have been the events of the 1960’s that brought him to ask more dangerous questions about broader social integration and rabbinical attitudes toward performing interfaith marriages, which at that time were still explicitly discouraged by the Central Conference of American Rabbis (CCAR).

I’m not sure when he officiated at his first interfaith wedding, but by the 1970’s he would speak on the subject publicly and told the Washington Post in 1979

If a Jewish person asks me to be present at such an important moment in life, I am not going to say no.

Starting early in the 1970’s he conducted research surveys of reform rabbis to see how many would officiate at an interfaith marriage. While the subject itself was controversial, the surveys made it more so, since it created a common knowledge problem: even the early evidence he published showed that many more rabbis would agree to officiate than was previously believed. He would continue to do this survey-based research for the next 40 years.

(One time he found a problem with the survey and asked me to debug the Windows 97 era Visual Basic that assembled the final survey results. He got frustrated I couldn’t salvage the decades’ old code base with thousands of lines of code in a language I’d never worked with before running on a different OS. “I thought you were good with computers!”)

In Deuteronomy, God tells the Israelites that they are a stubborn people, and Irwin understood this well; other rabbis were not easily swayed. The intermarriage research controversy did reach something like a crescendo in 1973. Jack Werthheimer describes the debate as follows:

… Irwin Fishbein pleaded with his colleagues to recognize that they did not have the power to prevent intermarriage by refusing to sanction such marriages; he urged them “not to slam a door that may be only slightly ajar” by refusing to officiate; and he called upon them to utilize their persuasive, rather than coercive, powers to encourage mixed-married couples to participate in Jewish life. …

Joel Zion portrayed “mixed marriage without prior conversion [as] a serious threat to the survival of the Jewish people.”

Zion’s rhetoric would be echoed by other contemporary rabbis like Ephraim Buchwald using inflammatory rhetoric likening interfaith marriage to a “Silent Holocaust”.

I like to think Irwin knew he had them on the run when he’d reduced his opponents to such hyperbole.

It takes a measure of courage to make a controversial contention publicly, or to contradict your colleagues. Few people are even capable of that; courage is the world’s scarcest resource. Irwin’s research and advocacy to normalize interfaith marriage was a significantly more radical project than anything like that. It was challenging an ancient and legally grounded religious custom of the world’s oldest extant monotheism.

Such advocacy in the 60’s and 70’s seems like ancient history. Did Irwin’s arguments about interfaith marriage end up winning the day?

Some Data

You didn’t suppose you’d make it though this substack article, even if it’s an obituary, without looking at data did you? Has Jewish life been subverted or diminished by interfaith marriage?

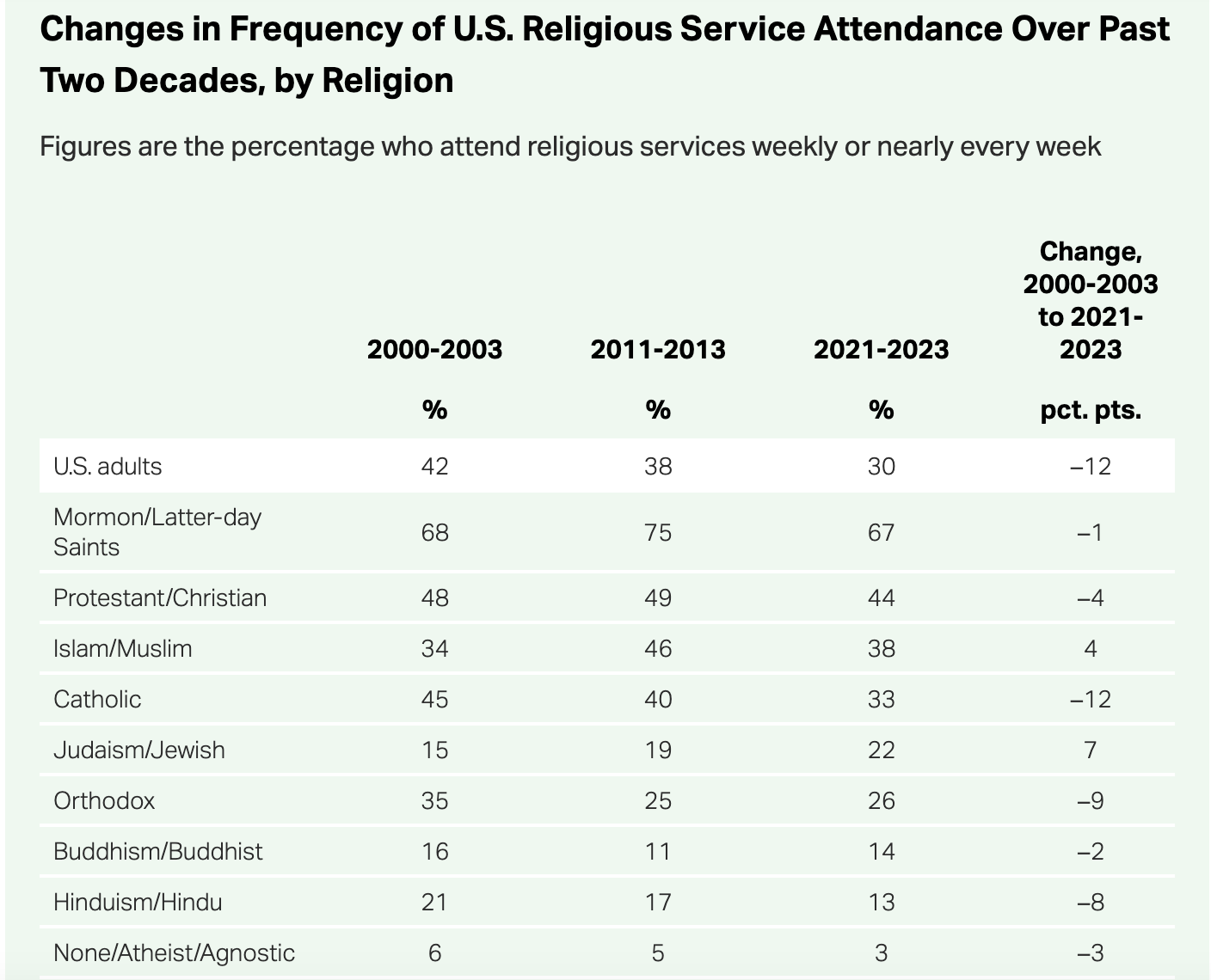

Since Irwin started performing interfaith marriages, the United States has seen a large decline in religious observance, and that’s accelerated since the new millennium. Gallup reports in two year aggregated periods that Judaism is one of the only exceptions to this rule.

This is suggestive and striking but doesn’t prove much apart from cultural Judaism’s staying power. Zion’s point in 1973, I think, was that intermarriage would dilute Jewish identity simply because people would not identify as Jews anymore. This just shows Jews who identify as such continue to be more religiously involved than other groups.

Demographic researchers at Brandeis reported in 2020 that Jews have maintained 2.4% of the US population since 1990. The US test of this is probably correct where there is less pressure on marriage behavior and fewer enclaves of highly observant orthodox Jews than in Israel. Pew reports that fully 42% of US Jews have a gentile spouse, so if the Brandeis estimates are correct, a maintenance of the population does not represent a “silent holocaust” or a “threat to the survival of the Jewish people”. The interfaith marriages that took place in 1990 have had a full generation to produce Jewish or gentile children, and the Jewish portion of the US population has been sustained.

Coda

Jews gaining the ability to marry who they wanted in the eyes of the rabbinate is now a hugely overlooked issue. Many have reform rabbis officiate at their marriage, and it would be an exaggeration to suggest that Irwin Fishbein invented modern intermarriage, but anyone in such marriages should know how the precedent for their union originated. I include myself in this privileged group. Irwin’s insight that harmony and accommodation would win the day over rejection and ostracism has been vindicated. I’ll miss him.